Beyond Artifacts: The Strategic Imperative of Design Communication

- William Haas Evans

- Jul 20, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 24, 2025

There is a moment in every new product design when everything changes.

Not the moment when the final prototype ships. Not when the user testing validates your riskiest assumptions about how something might be interpreted and used. Not even when the board approves funding based on your compelling demo.

No.

It's the moment when someone who wasn't in the room looks at your wireframe and understands. Someone who missed the late-night debates. Who never saw Post-its covering every wall. Who wasn't there when design decisions emerged from creative chaos. They look at your wireframe and understand not just what you designed, but why you designed it. And why you designed it that way.

This moment, this transfer of design intent from one mind to another, determines whether innovation succeeds or fails in organizations. It's the difference between Southwest Airlines' napkin sketch becoming a $30 billion business and countless brilliant concepts dying in implementation.

Yet most organizations treat wireframing and prototyping as documentation activities. Hand-offs. Rather than what they truly are. Strategic weapons in the war against organizational entropy.

This is wrong.

And expensive.

Potentially fatal.

The Hidden Crisis in Design Translation

My old friend Jon Kolko argues that "Interaction Design is the creation of a dialogue between a person and a product, system, or service." But there's another dialogue we've catastrophically ignored. The conversation between design intent and organizational action. Between abstract vision and concrete implementation. Between the future we imagine and the future we build.

Consider the brutal economics. Nielsen's research shows that fixing design problems in production costs 10 to 100 times more than addressing them during design phases. IBM found that every dollar spent on design returns $100 in value. But only if that design intent survives the journey from concept to customer.

Yet most organizations treat wireframes as throwaways. Prototypes as checkboxes. Design documentation as bureaucratic burden tossed on the funeral pyre of the last digital transformation to agile.

The result? A graveyard of good ideas poorly executed. Littered across the customer experience. Innovation initiatives that fail not because the thinking was wrong, but because the thinking never made the leap. Across organizational silos. Time zones. Cognitive frameworks. Design intent evaporates in translation like morning mist. Leaving bewildered development teams to guess at ghosts of meaning.

This is what Henry Mintzberg warned us about with strategic planning. The fatal disconnect between thinking and doing. But while Mintzberg focused on the temporal gap, plans made today for futures that never arrive, design faces a cognitive gap. Brilliant synthesis in one mind that must somehow replicate itself across dozens or hundreds of other minds. Different perspectives. Different interests.

The Fidelity Trap and Buxton's Insight

Bill Buxton's insight should have transformed design practice. "There is no such thing as high or low-fidelity, only appropriate fidelity." Instead, we've largely ignored its strategic implications.

Every wireframe becomes a decision about communication depth versus resource investment. Every prototype becomes a choice about what to reveal and what to conceal. What to test and what to assume.

The fidelity trap catches designers in a vicious cycle. Low-fidelity artifacts invite feedback but fail to communicate nuance. High-fidelity artifacts communicate nuance but discourage feedback by appearing finished. Most critically, both approaches optimize for the artifact rather than the understanding it should create. The trade-off decisions it should enable.

Roger Martin calls it a comfort trap. We focus on what we can control. Pixels. Interactions. Visual polish. Rather than what matters. Shared understanding. Aligned action. Organizational learning. We perfect our deliverables while our ideas die in translation.

Synthesis as Strategic Capability

Design synthesis provides the escape route from this trap. What I define as making meaning through inference-based sensemaking. But synthesis isn't just about organizing research findings into neat frameworks. Published in PowerPoints on SharePoint. Thereafter forgotten.

It's about transforming human insights into design constraints and assumptions. Embedded in rough sketches and prototypes that can survive the journey. Mind to mind. Team to team. Sprint to sprint.

This requires reconceptualizing wireframes and prototypes entirely. They're not static representations of future states. They're dynamic vehicles for transferring cognitive models. The annotation becomes as important as the interface. The rationale embedded in the artifact becomes as critical as the pixels on the screen.

Corporate design education focuses on craft. Composition. Hierarchy. Interaction patterns. Best practices. These are necessary but insufficient. The missing piece is what Donald Sull calls simple rules. Heuristics that can guide decision-making when the original designer isn't in the room.

How do we embed simple rules into sketches? How do we build prototypes that teach principles, not just verify or validate features?

Schneidermann's Insight and Its Implications

Ben Shneiderman, a pioneer in the product design world, has a great line. "If a picture is worth 1,000 words, a prototype is worth 1,000 meetings." This hints at something profound that most miss.

Prototypes don't just save time. They create what Karl Weick calls sensemaking devices. Artifacts that help organizations understand not just what's being built, but why it matters and how it connects to larger purposes.

But here's the insight from Ben. Prototypes teach only what they're designed to teach. A prototype optimized for usability testing won't automatically communicate business model innovation. A wireframe focused on information architecture won't necessarily transfer brand strategy. This is where strategic thinking separates great designers from merely good ones.

The notion of "just enough" prototyping misses half the equation. Yes, prototypes should command only the resources needed to generate useful feedback. But they should also embed sufficient context to preserve design intent across organizational boundaries. This isn't efficiency. It's effectiveness.

The Double-Loop Learning Imperative

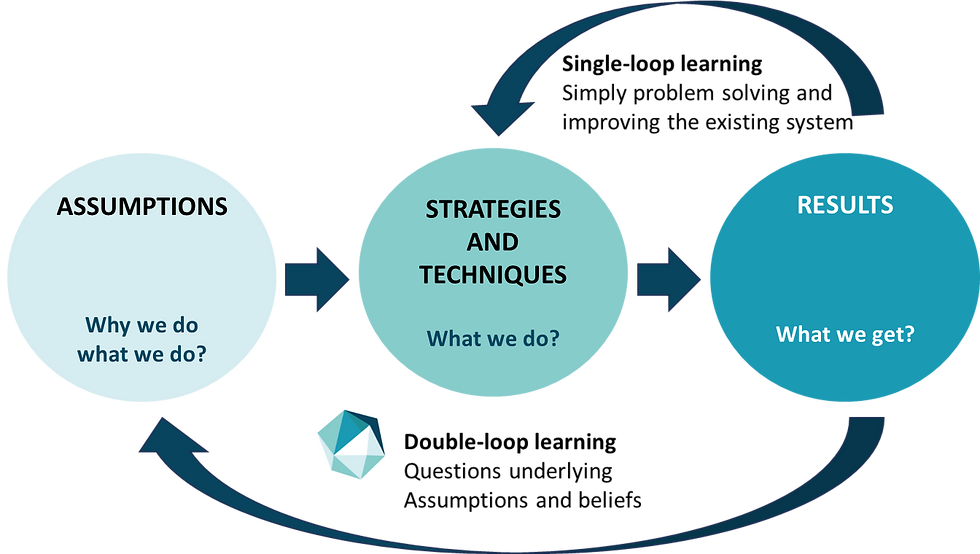

Donald Schön's concept of reflection-in-action describes professionals who examine their thinking while solving problems. But strategic design requires double-loop learning. Questioning not just tactics but underlying assumptions if it's going to enable organizational learning and adaptability.

Single-loop learning improves technique. Better wireframes. Slicker prototypes. Smoother presentations. Double-loop learning questions purpose. Why are we sketching this? Why do we wireframe this way? What assumptions are embedded in our prototyping process?

How are we countering confirmation bias? Group think? Premature convergence for political expediency? How do our artifacts shape organizational thinking beyond their immediate purpose?

This distinction becomes critical as technology transforms design work. AI can generate wireframes. Automated tools create interactive prototypes. Code emerges from Figma files. What can't be automated is strategic judgment. Knowing which problems to frame. Which assumptions to test. Which organizational capabilities to build through design artifacts.

The assertion that "good design changes behavior for the better" applies not just to end users but to organizations themselves. Strategic wireframing and prototyping change how teams conceptualize problems. How stakeholders evaluate solutions. How organizations learn from experimentation.

Single-loop learning improves technique: better wireframes, slicker prototypes, smoother presentations. Double-loop learning questions purpose: Why are we sketching this? Why do we wireframe this way? What assumptions are embedded in our prototyping process? How are we countering confirmation bias, and group think, and premature convergence for political expediency? How do our artifacts shape organizational thinking beyond their immediate purpose?

This distinction becomes critical as technology transforms design work. AI can generate wireframes. Automated tools create interactive prototypes. Code emerges from Figma files. What can't be automated is strategic judgment—knowing which problems to frame, which assumptions to test, which organizational capabilities to build through design artifacts.

The assertion that "good design changes behavior for the better" applies not just to end users but to organizations themselves. Strategic wireframing and prototyping change how teams conceptualize problems, how stakeholders evaluate solutions, how organizations learn from experimentation.

Systems Thinking at Scale

The challenge compounds exponentially as design scales. Individual designers maintain intent through direct communication and personal knowledge. But when design systems serve multiple teams across continents, when prototypes guide development across time zones and quarters, when wireframes must be interpreted by people who weren't just absent from the room but haven't even met the designers, then communication becomes capability, not just skill.

This is where systems thinking becomes essential for design leaders. Every wireframe exists within a larger ecosystem of artifacts, processes, and cultural assumptions. The wireframe that makes perfect sense within your team's context might be incomprehensible to the development team implementing it six months later in Bangalore. The prototype that effectively tests user behavior in San Francisco might completely fail to communicate business logic to stakeholders in Shanghai.

Gary Hamel's work on management innovation applies directly here. Just as the most powerful management innovations are often the simplest, like the moving assembly line, the most powerful design communications are often the most elemental. But achieving simplicity requires understanding complexity. Knowing what can be stripped away because it's embedded in organizational knowledge. And what must be preserved because it's essential for action.

The Architectural Parallel

Jesse James Garrett's observation that "a wireframe is like a blueprint for a house" deserves deeper examination. Architects don't just create beautiful buildings. They create documents that enable hundreds of professionals to collaborate across months or years to realize a vision. The blueprint preserves architectural intent through inevitable changes. Constraints. Interpretations.

But architecture has centuries of evolved practice for this preservation. Design has decades at most. We're still learning how to embed intent into artifacts that must survive not just handoffs but organizational restructures. Strategy pivots. Team turnovers. We're still discovering how to create what Mintzberg calls adhesive strategies. Ideas that stick because they're embedded in artifacts that teach.

The Strategic Designer's Mandate

The future belongs to designers who understand their primary output isn't wireframes or prototypes. It's organizational capability for innovation. The artifact is just the vehicle. The real product is what Peter Senge calls shared mental models that enable coordinated action despite complexity.

This requires treating wireframing and prototyping as strategic acts, not just craft exercises. It requires developing synthesis capability that transforms research insights into design principles that persist through implementation. It requires building reflective practice that questions not just what we design, but how our designs shape organizational thinking.

Most critically, it requires recognizing that in a world where, as Marc Andreessen says, "software is eating the world," the ability to transfer design thinking across organizational boundaries becomes the ultimate competitive advantage. Companies that can preserve and propagate design intent will outmaneuver those that can't. Teams that can learn from prototypes will outpace those that merely build them.

From Artifacts to Dispositional Advantage

Ultimately, this isn't about tools or techniques. It's about developing strategic communication capability that transforms design from service function and cost center to leadership discipline.

That moment when someone understands not just what you built but why you built it that way isn't magical. It's designable. It's the product of intentional choices about how we embed meaning into artifacts. How we structure learning through prototypes. How we preserve intent across organizational distance.

This is learnable.

In Part II, we'll explore how this strategic design capability becomes the foundation for something even more powerful. Using wireframing and prototyping not just to communicate today's designs, but to sense and explore tomorrow's possibilities. How design artifacts become tools for strategic foresight in a turbulent world.

Because as twenty-seven executives in a crisis discovered, sometimes the best way to think about the future isn't to analyze it.

It's to sketch it.

Very thought provoking!